In October 2004, Temas published the article “Havana 2050 “ by Carlos Garcia Pleyan. Ten years later, the author returns to the same topic to analyze how much the issue has changed – or not – in a decade, and propose solutions and strategies. With this article, Catalejo begins a series designed to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Temas, with writings to update issues discussed in the pages of the magazine in the last two decades.

Is the city of Havana already an impossible equation, a problem without solution, a hopeless muddle? I take the controversial title of one of the latest books written by Jordi Borja (The City, an Impossible Equation [1]) to highlight the dramatic situation of what was once known as the “Key to the New World.” An affirmative answer to that question would be morally, politically and historically unacceptable. There can be no justification for apathy faced with the growing needs of its people, or ignorance and disdain for the country’s largest concentration of culture, productivity and knowledge.

It is now urgent to change the terms of the Havana equation. To the extent that they continue allocating insufficient resources for its rehabilitation, in which local governments remain weak, in which active citizen participation is not promoted and encouraged, one can only expect on the other side of the equation our old, broken and tired city.

The built city and its social fabric is one of the most complex and valuable cultural products in the history of any country. The issue of relations between city and society has encouraged the central debate of urban sociology since its inception. It's commonly accepted that although the city is a social construct – given that one can read a collective history in its structure and functioning – it is also true that this built, dense and diverse environment has a strong impact on social behavior in terms of personal freedom, variety of choices, innovation etc.

Hence cities are not only built historical products, but also collective processes in evolution. Many subjects – governments, enterprises, families and social groups – affect the city by commission or omission, adding or removing stones, legitimizing or censuring behaviors and values. In a way, building citizenship is to define the boundaries between legitimate and illegitimate, legal and illegal and formal and informal. It is a continuous process of formulation and reformulation. There are times in which majority consensus materializes and stabilizes, and times of crisis and change. In Havana we are in one of these. The rules of the game are not clear. The informal city has great weight in the economy, construction, work, transport, language and values. The impact of the Special Period has dismantled a project and a social pact, which is in the process of re-articulation.

WHAT ARE THE ESSENTIAL FEATURES OF HAVANA’S CURRENT SOCIETY?

I will attempt to provide a brief assessment and put forward some ideas about the ingredients that should be changed in terms of the equation in order to overcome the current situation.

An essential characteristic of the capital’s society today is that about half of its residents were less than 10 years old in 1990 [2]; thus half its population came of age in the Special Period. One of every two Havana residents not only did not know the capitalist era but also did not live through the radical social improvements achieved in the first thirty years of revolution. For many of them, living in Cuba is associated with economic difficulties, decline of social consensus and the discrediting of the values of work, solidarity and honesty. The structure and behavior of this social group is the result of both the crisis and the measures taken to overcome it such as self-employment, dual currency and the introduction of market relations. This has been shaping a new social, demographic, income and values structure as well as new dynamics of upward and downward social mobility and new patterns of inequality.

DEMOGRAPHIC EFFECTS

First, there has been a radical change in demographic trends. Havana’s population in 2014 is the same as in 1990, almost a quarter century later. Not only has natural growth declined to zero (each year 20,000 residents are born and die in the city), but there is a net loss from migration (about 12,000 people move from other provinces annually to Havana, but 18,000 go abroad. The city loses annually an average of 6,000 residents). [3]

Second, there has been a sustained and progressive process of “dehavanaization” and ruralization of Havana’s population. There has been a combined effect of the early emigration of the upper bourgeoisie and part of the middle classes, and the subsequent departure of residents born in the city. Today two-thirds of those leaving are between 15 and 34 years old and more than half have completed high school or university; population coming from other provinces have a significant rural component and lower levels of education. This means that habits, behaviors, tastes and patterns of other habitats have been transmitted to urban culture. According to the 2002 Census, residents born in the city were less than half of the total. [4]

Third, the aging of the population is alarming. The national trend is more acute in the capital where, in 1960, there were seven young people for each elderly person. By 2020 it is estimated that there will be two young people for each older person, with the related effect on the demand for health services and specialized support, greater burdens on social security as well as an increasingly worse dependency rate.

Fourth, and a corollary of some of the already explained phenomena, family size has been steadily declining. Between 1970 and 2002, couples with children have declined from 62 percent to 45 percent. Childless couples and single-person households have increased from 25 percent to 37 percent, while single-parent families have tripled from 4 percent to 12 percent. The average household size in Havana in 1970 was 4.5 people, while in 2012 it had dropped to 2.8. [5]

ECONOMIC EFFECTS

The measures taken to overcome the crisis have had undeniable impacts on city life. The expansion of the non-state economy has generated greater diversity of shopping, dining, housing and transportation, but also accompanied by urban deterioration and extensive and abusive invasions of public space as well as assaults on urban aesthetics.

The increase of informal networks in the labor market, in financing (e.g., through remittances) and in marketing products and services is evident. Moreover, the economic base of the capital has also undergone a radical transformation by strong decapitalization and technological obsolescence of much of the industrial, storage and transport facilities and infrastructure.

SOCIAL EFFECTS

On one hand, a freeze on social spending is evident [6], with overall budget cuts and increased targeting of subsidies in areas such as food or housing. On the other, the liberalization of free-market sales (houses, cars) and travel abroad, and the commodification of many services in the education sector (private tutoring), health (dentists), transport (the “almendrones,” private group taxis on fixed routes), trade (the “merolicos,” street vendors), culture (DVD sales, 3D cinemas, distribution of the “paquete,” package of audiovisual programs) has contributed to increasing social heterogeneity and stratification. About 5 percent of the Cuban population – more than half a million people – constitutes an emerging middle class who take vacations in Varadero, while about 25 percent are in a degree of vulnerability that in other countries would be called poverty, particularly those families who depend solely on a state salary or pension. This often coincides with gender patterns such as single mothers or skin color. It is known that these groups receive a negligible proportion of total remittances.

At the same time, there has been an erosion of representative structures. The local levels of People’s Power have very few powers in a centralized, top-down structure and limited resources to respond to the demands of the population. Unions and mass organizations are languishing and all this results in decreasing levels of interest in social participation. Moreover, the geographic polarization of economic development in tourist or special areas such as the Mariel tends to increase migration towards urban poles, which generates increased demands for housing and social infrastructure.

PHYSICAL EFFECTS

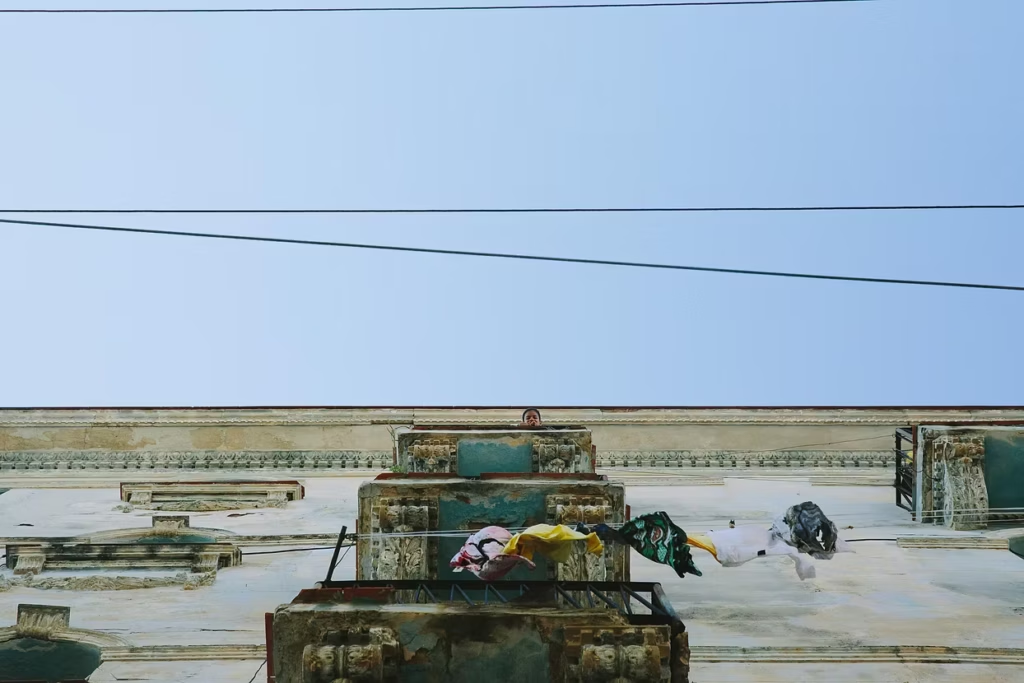

The physical appearance of the city in most neighborhoods is deplorable, with the honorable exception of the historical center being rehabilitated and some well-maintained areas of Miramar and Siboney.

The deterioration of urban infrastructure has exceeded permissible limits. The fragility of the city faced with technological risks such as energy or communications breakdowns, and natural risks like flooding due to poor or nonexistent drainage and the downing of over-head power lines by strong winds, is becoming ever more dramatic and overwhelming.

The increasing “formalization” of the informal economy in small family businesses or cooperatives in various sectors of production and especially services resulted in a greater diversity of supply, but quite often low quality buildings and designs have affected urban aesthetics. There are considerable deficiencies in repair, rehabilitation and construction of housing. While the city hosts 20 percent of the country's population, the state only devotes 11 percent of its new residential construction – 4,000 housing units – for a population of more than 2 million people). [7] While about 2,000 units become available annually by emigration, another thousand are lost through building collapses.

Liberalizing home sales to some extent has eased the rigidity of a market dominated by home ownership, the absence of state rentals and house swaps which had been the only legal mechanism available for matching supply to demand. However, the market is segmented by the entrance of outside capital (not only from the Cuban community living abroad), which has generated two markets: one with high prices and high-quality properties and another, at lower prices, for local demand.

One effect of this segmentation is the displacement of families occupying quality homes to houses in worse shape, smaller homes or ones in the outlying areas, to monetize the difference so as to improve their standard of living. State building is targeted to specific groups with condominiums for doctors and military officers, while the population living in shelters grows with each storm that hits the city. [8]

SOCIAL AND POLITICAL DEBATE IS ESSENTIAL

The degree of accumulation of problems and the interrelation among them requires greater public debate. There are topics about which it would be difficult to determine proportions or trade-offs that would be socially acceptable without a public discussion that forms a social consensus.

We are dealing with stress points that should not be seen as contradictions:

• What are the levels of inequality that Cuban society is willing to tolerate as a result of the introduction of market relations, what levels of spending can the country afford for social programs for protection and equity and, therefore, what is an acceptable burden on the budget?

• How to determine an appropriate balance of centralization at ministerial levels with the need for decentralization of powers, skills and resources to provincial and municipal governments – in particular, the responsibility of deciding on and implementing local investments?

• What legal and economic powers – levels of savings, investment, spending on wages – are transferred to the autonomous initiative of state enterprises and what should be state regulation and planning functions that are kept at the central level?

• What proportion is appropriate in each instance between consumption levels and improving living standards of the population and levels of accumulation and investment to ensure the development of the nation?

• What is the appropriate ratio between investment levels in Havana and the rest of the country, particularly regarding housing?

These are all issues that affect the present and the future, not only of the capital but of the nation, and deserve broad debate among political leaders and citizens.

“As a well-known Brazilian mayor and urban planner noted, ‘The city is not the problem, it is the solution'”

I asked at the beginning of my piece if the situation of Havana constitutes an impossible equation with no solution. I do not think so. I think there are feasible answers, but only if there is renewed focus on multiple issues and if bold and innovative decisions are made. Below I set out what are, in my opinion, those keys to the future without which it will be impossible to break out of the current predicament.

FIRST, RECLAIM THE VALUES OF THE CITY

In the early years of the Revolution there was an anti-capital feeling among some of the population who did not live in Havana, understandable due to the vast inherited imbalances in living standards between Havana and the rest of the country, particularly in rural areas. Moreover, tourism and recreational activities in the capital, which were increasingly related to the mafia, prostitution and administrative and political corruption justified that anti-Havana feeling. The predominantly peasant origin of the Rebel Army only increased this aversion to urban life. Half a century later, that pro-rural approach, which still sees the city as a den of corruption that lives parasitically off the economy of the rest of the country, makes no sense. It is finally time to overcome that approach that has done so much damage to the city. Even today one can read in the official press, writings of leaders who consider rural, rather than urban, life more “reasonable.” [9]

It has been noted that the concentration and diversity of material and intellectual resources that interact in the city make it a highly productive center. It should be seen as the main source of employment, wealth generation, scientific development and cultural expression in the country. The city is one of if not the most complex cultural products. Often it has been argued that these assertions are dangerous and unfeasible in the sense that the city itself is endangered by its unquestionable appeal. It would be counterproductive, according to this point of view, to invest in cities because greater investment makes the city more attractive, resulting in more in-migration and more demand for further investment. That presumed vicious cycle is more myth than reality. On the one hand, solutions will have to be found given that urbanization is an irreversible global trend. On the other, the supposedly disturbing depopulation of rural areas has not been a threat at all to agricultural production. Current technological levels allow agricultural economies to have small labor forces devoted to those activities. Uruguay, for example, a country of 3.4 million people, with 2 million of them residing in the capital, Montevideo, and a rural population of 7 percent, is a country with such a strong agricultural sector, exporting USD $6 billion annually in agricultural products and the sector has grown since 2000 at a rate of 18 percent annually. In contrast, agricultural employment in Cuba still represents 20 percent of the total and only produces 3 percent of GDP, with imports of billions of dollars needed. Therefore, the anti-urban economic argument is demonstrably weak. As a well-known Brazilian mayor and urban planner noted, “The city is not the problem, it is the solution”.

SECOND, GIVE THE CITY A TRUE LOCAL GOVERNMENT, WITH RESPONSIBILITY OF MANAGING ITS OWN PLAN

We have defended the role of planning in running the present and future activities of the city, but it’s necessary to recognize that at present the plan and budget that are actually implemented do not go much beyond a mixture of sectoral decisions, at times inconsistent, both in the order of their timing and in particular from a geographical point of view. It is essential to “localize” to a much greater degree administration, plans and budgets. Achieving this means moving in two directions.

It is necessary to update the approaches and methods of planning, so as to better coordinate the strategic plans with operational ones. The former are a mere compendium of largely unachievable desires and good intentions, and the latter, a list of short-term sectoral decisions. It must be stressed in particular that the plans should not only define what to do, where, how and when, but with what and with whom. Plans not only suffer from a surprising ignorance of financial and material resources required for implementation and are frequently disconnected from the budgets, they also do not create the necessary links with institutions, state enterprises and entities that would be implementing them. At the same time, we must avoid, with the same determination, administering and managing resources detached from the plan. Failing this, the structural responses remain divorced from investment programs.

In addition, it is not enough to defend local and provincial budgeting, and coordination between planning and management, because it does not make sense without also democratizing urban management. It is necessary to see urbanism not only as a planning technique, but above all, as public policy, as a public service. We must rethink the relationship between the administration and citizens, and introduce participatory planning and budgeting. Citizen and democratic oversight over decisions related to the city is essential, updating accountability sessions (1). We will have to reflect on the political and administrative organization of an urban area the size of Havana that would maintain authority at the metropolitan level, but bring administration and oversight closer to citizens and study the possibility of establishing districts coordinated with People’s Councils (2). We must take into account that almost all the municipalities of the city have more than 100,000 inhabitants and three of them more than 200,000. Similarly, we must think about a new division of labor between the public and private sectors, as well as the responsibilities and powers government agencies and state-owned enterprises.

All this will lead, necessarily, to review and strengthen urban regulations and urban law.

THIRD, INCREASE FUNDING SOURCES

It is impossible to address the city’s many problems with the level of resources devoted to it today. The first move would be to correctly calculate and really know what would be the cost of reconstruction.

Economic idealism, which from the beginning was a feature of financial resources management, along with the current complexity of any accounting calculation due to the existence of two different currencies and exchange rates, makes any estimate extremely difficult. To provide a sense of the magnitude, the most recent estimates of the need for investment for the city exceed 16 billion, more than a quarter of the national GDP over a fifteen year period. It is not only difficult to estimate the cost of the necessary reform, but it is even virtually impossible to estimate the real cost to build a house due to price distortion.

Faced with this kind of situation, it is essential to open all possible avenues of funding from local to international. Small but numerous local, community and family resources must be made available, whether from the savings and transfers from abroad, and not only material and financial resources but also human and intellectual resources. There are now state-owned facilities in many neighborhoods that are vacant and unused that could be taken advantage of. They should revert to municipalities so that they could reactivate them using public or private funds and then rent them out for non-state uses. The same could be done with some of the vacant land available. Finally, an almost entirely unused resource is a variety of broad local taxes and fees.

It would also be of economic interest to increase transfers from the national budget to the most productive territory of the nation, or at least try to pay down the debt that has accumulated for half a century with the capital. There should be a provincial budget that could be administered by the city government. At present, the city receives more than 3.4 billion pesos from the national budget, but only spends 2.3 billion. The provincial budget is allocated 100 million annually for locally targeted investments, while ministries are investing some 2 billion in the city based on sectoral criteria, which are not always coordinated or relate to each other.

Finally, we must get beyond the apparent incompatibility between foreign investment and national sovereignty. There’s no reason foreign investment is acceptable when it fosters national resources such as nickel, oil, tourism, tobacco, rum or sugar, and unacceptable when it comes to enhancing urban resources to benefit the country and the city. The rehabilitation of Old Havana is evident proof of this, although admittedly the country is insufficiently prepared for it. Most of our planners know how to plan, design and regulate, but very few are prepared to negotiate, nor are they are in a position to do so. There are no clear methods for land value appraisals; property and land registries are deficient; instruments to recover some of the profits from urban land are virtually nonexistent. It doesn’t make sense to shout to high heaven about the real estate business, but rather we must learn to use it wisely, as is being done in other sectors. The most recent example is the Mariel special zone. The scale of the city’s problems and the considerable resources necessary for their solution do not allow us to ignore any funding sources whether local, national or international.

FOURTH, RENEW THE ECONOMIC BASE

Strengthening the economic base of the city does not have to repeat the policies that were valid at other times. It is necessary to promote a new economy, going from the industrial city to the postindustrial city and knowledge city. The level of education and creativity achieved by the population makes it possible to promote creative economies based on innovation in production and service sectors such as biology and pharmaceuticals, information technology and application programming, design at all scales and specialties and cultural activities in all art forms and related products. These are activities for which the population is trained and clearly are located in urban areas, offering employment with less associated need for transportation, energy and land than traditional industry and with less pollution.

Naturally, to achieve this it will be necessary to modernize infrastructure, but it is no longer only to modernize electric grids and gas and rail lines as during the industrial revolution, but essentially improve mobility, both physical and virtual. Today one of the factors that most increases the costs of production and operation of the city is the huge and useless waste of time. This is one of the largest reserves of efficiency that Havana should have today. The deficiencies – particularly of public transport and, to a lesser extent, the telephone networks’ cumbersome, slow and absurd administrative procedures; and the virtual absence of Internet access – generate a dramatic waste of time that is difficult to quantify. It would require a determined and clear political willingness to reverse the situation. And it’s not just the citizens’ right to information and knowledge, but that connectivity is the basis of the modern economy. From large state-owned enterprises to small and medium-sized private and cooperative ventures, they need such connectivity to revitalize access and enter into an extremely competitive market. Every day that passes it is more difficult to conceive of developing society without developing connectivity.

Moreover, the current expenditure of time for the transport of persons, goods, information and financial securities within the city is unsustainable. Currently the cost resembles those of large metropolises of tens of millions of people and thousands of square kilometers, when Havana is a small, relatively dense city. Either financing is found to create an efficient public transport system, or it will be necessary to start very costly urban surgery – not only from a financial point of view, but above all, the built environment, which is an essential resource of the city – to build highways, tunnels, road junctions and parking structures, which in the end, will not solve traffic problems, but make them worse, given that they facilitate private transit and this encourages greater privatization of urban transport.

FIFTH, SUPPORT BUILDING A STRONG SOCIAL FABRIC

Achieving activation of the main resource of the city – Havana residents – means encouraging and facilitating associations of citizens from below, whether based in neighborhoods and communities or by professional or cultural interests, age groupings or other social affinities. We must take into account that the city now has a new demographic profile in terms of age structure, level of education and family structure, while values and social norms, as well as associations and social institutions, have not evolved at the same pace. It is ever more urgent to revitalize or replace the top-down bureaucratized mass organizations. Even the growing and sustained emigration of well-educated young people is related to the current difficulties of participation by new generations in economic, social and political life. The complexity and creativity of the urban social fabric is what can really activate the enormous latent reserves of initiative and innovation.

SIXTH, LOOK INSIDE, IDENTIFY AREAS OF OPPORTUNITY

Havana has huge internal potential. A number of large urban facilities, such as several railway terminals, port areas, airports, big warehouses, former military installations, large obsolete industrial infrastructure or entire areas are no longer functioning. This opens up the possibility of conceiving and promoting major urban development projects that could not only attract investment but could foster structural changes in the city. As an example, just think of the formidable prospects opened by the deactivation of Havana’s port and the scenic, recreational, environmental, cultural, tourism and real estate opportunities contained in the 18 kilometers of the bay’s coastline and its 1,700 hectares of land. This not only would restore the image and use of the bay to the city’s inhabitants, but would also make possible financing for a number of infrastructure projects that Havana urgently needs.

Near the city there are also no less important potential projects. The north coast, running along hundred kilometers from east to west, has many excellent bays – like Mariel – and extensive beaches that provide huge economic potential (in tourism, transport, industry and more which is absurd to waste.

We must also look inward, with the express intention of “making city over the city”; It is already more than proven that a dispersed city is more expensive than a compact city in terms of energy consumption, transport, water, land and infrastructure networks. We must develop and modernize while minimizing costs of occupying new land. Moreover, we must and can optimize land use, built and unbuilt, through taxing misuse or non-use of land and buildings. Too many facilities are now closed and unoccupied, or have negligible uses – in particular government agencies at all levels such as ministries and provincial and municipal departments. Too many buildings are misused with services converted into housing and housing into services. This year a tax on the unused agricultural land has already gone into effect, but it would have made even more sense to have introduced one for the non-use of buildings and urban land.

Within the city, we need to look in particular towards those most disadvantaged and neglected areas. Once we have liberalized not only house building, but also the residential real estate market, we should refocus efforts and public resources in areas with severe deficiencies. For example, it would mean focusing on providing infrastructure for areas south of the city, or in rebuilding neighborhoods like Centro Habana, tasks that, in no way, can individual or family initiative undertake, since they require plans, resources, technologies and equipment that are not within technological or financial reach.

SEVENTH, LOOK OUTSIDE, REPOSITION THE CITY IN THE REGION

We must also open our eyes to the world and, specifically, to our region. At the beginning of the 20th century, Havana was a city of 300,000 inhabitants, while Miami was a village that barely had 2,000. At the time of the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, the two cities had the same population size of 1.5 million inhabitants. By the 21st century Havana had 2 million and Miami over 5 million. For nearly four centuries, Havana was the “key to the new world.” Miami is now undoubtedly the dominant city in the region. One of the bets that Havana should place in the coming years is precisely to try to recover the role of regional communication center wrested away by Miami and Panama City. The new port of Mariel can be a good start.

To achieve this, we must rethink the relationship between the cities of Havana and Miami and, in particular, the links to the Cuban community in the State of Florida. Today there are about 700,000 former Havana residents residing in Miami, more than half of those who arrived after 1990; 1.2 million Cubans live in Florida and 1.8 million in the United States. It is true that this is an operation with both risks and opportunities, but no less than previous experiences – see the examples of overseas Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese communities – which indicate that the advantages of being able to have the financial capital and knowledge of these communities has overcome the inherent risks. There are no compelling reasons for Cuba’s case to be different.

In recent years, a cross-border space with flows of different types has been forming. Personal exchanges between the Cuban community based in the United States and Cuba residents are increasing considerably. In recent times, more than half a million Cuban Americans and over 100,000 Americans a year have travelled to Cuba annually. In 2013, almost 100,000 Cubans visited the United States – there are more than 300 flights monthly – and these flows will increase dramatically the day restrictions on US tourism to Cuba are lifted. Cuba has been providing a young and skilled labor force and Miami has begun returning retirees to live the rest of lives in their homeland. It should be added that trade in goods, are not limited to the hundreds of millions of dollars of government food imports; informal imports of goods that nourish new private businesses and private households are growing. and already exceeds 1 billion dollars.

No less significant are the financial flows from the United States. Remittances already exceed 2 billion dollars and are intended not only for family consumption, but have begun to provide financing to start small businesses. In addition, remittances are spent in the new real estate market through relatives or front men, or are used for home building or repair. Nor should we forget the movement of information, whether in terms of “canned” cultural products – movies, TV, video, series, novels, music, etc. – or even the field of the imaginary, taking into account the accumulated tension in decades of estrangement, conflict, longing and fantasies. We must also be attentive to those hidden or illegal flows – the risk of diseases and epidemics, drug trafficking, smuggling or trafficking of illegal immigrants – whose effects can be devastating given two such asymmetric realities .

While Havana offers unquestionable comparative advantages for growing exchange and trade such as public safety, adequate levels of health, rich culture and heritage, natural beauty and hospitality, the fact remains that it also has a number of weaknesses. These range from entrances to the city – deficiencies and inefficiencies in airports, customs, marinas, immigration procedures, transport and domestic and international communications – to the regulatory, administrative and technological weaknesses that limit or hinder exchanges – for example, automated financial transactions, real property registration, etc. – all compounded by the absurd blockade laws.

However, despite the difficulties mentioned, it is easy to predict the future coming together of a northern coastal strip, which would include bays, ports, marinas and beaches from Bahia Honda, Cabañas, Mariel and Baracoa to Havana, Santa María del Mar, Jaruco, Matanzas and Varadero. This would constitute the appropriate regional framework for urban revitalization. It is a strip of almost two hundred kilometers, equivalent to that which runs from Kendall and Homestead to Boca Raton and North Palm Beach, Florida. Becoming the backbone of this region is an opportunity that Havana cannot lose.

THE DEBATE THAT AWAITS US

Defining and directing the future of the city will not be easy, but it presents exciting challenges. There are many issues that must be understood and deserve and demand a broad national debate. Here are some of them:

• How can we balance state investments between the opportunity offered by attractive potential on the northern coast mentioned above and the need to satisfy our obligation to address the needs of the central area and those on the southern outskirts of the city?

• How can we preserve and rehabilitate the enormous urban heritage of the city and make it compatible with the inevitable growth of private and public transport?

• How to overcome existing weaknesses in terms of issues like legislation, land registration and taxation to attract real estate investment that contributes to the renovation of urban infrastructure and built heritage?

• How can we manage to preserve the quality and diversity of national culture in all its manifestations – artistic, historic preservation, urban and values – against possible trivialization resulting from the growing opening to tourism, trade, exchange and globalized culture?

• How can we establish a common space – both state and civil – that is cross-border and interdependent with our northern neighbors, without being distorted by asymmetries and excessive imbalances?

These are just some of the challenges that will face the new generations of Havana residents. I would like these ideas to serve as a stimulus to participate in the debate and to support the recent appeal by architect Mario Coyula in one of his last interviews. When asked what should we do in Havana? he said “Cry for it, shout out for it, fight for it, although there is no hope of success. Demand profound changes in the causes that have led to physical, social and moral decline.” [10]

Originally published in October 2014, Catalejo.

Carlos García Pleyán is a Cuban sociologist, professor, and researcher. He holds a PhD in technical sciences. He worked for over thirty years as a civil servant and researcher in urban and territorial planning for Cuba’s national Instituto de Planificación Física (IPF) and Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Económicas (INIE), as well as for several Cuban non-governmental organizations (MEPLA and HABITAT-CUBA). Previously, he was an associate researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne. He has published a number of articles and he has given lectures on regional,

urban, and community development issues in various Cuban, European, and Latin American universities. From 2002 to 2011 he coordinated the local development program of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation in Cuba (Agencia Suiza para el Desarrollo y la Cooperación en Cuba, COSUDE). He has been a Professor at Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC), Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña (UPC), and Universidad Técnica José Antonio Echeverría de la Habana. He currently serves as advisor for COSUDE and Havana’s Office of the Historian (Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad de La Habana).

(1) Translator note: Municipal delegates are required to report back to their constituents and hear their input in semi-annul “accountability sessions”

(2) Translator’s note: People’s Councils are government entities covering districts smaller than a municipality that help coordinate, but do not administer or have their own resources.

[1] Jordi Borja, The City, an Impossible Equation, Icaria, Barcelona, 2013.

[2] Census of Population and Housing, 2002.

[3] Figures from the demographic and statistical yearbooks of ONE [Oficina Nacional de Estadística, National Statistics Office]. 2013. Most likely, this trend has increased since 2013 due to changes in immigration law.

[4] Census of Population and Housing, 2002.

[5] This does not mean an improvement in housing standards, since the livable space in these “houses” is unknown.

[6] Between 2008 and 2012, the budget allocated to education, health, housing and social assistance decreased by 10 percent, while social security increased by 23 percent due to the aging of the population – and the defense and law enforcement budget grew by 59 percent! See the Anuario Estadístico Nacional [National Statistical Yearbook] 2013, ONE, 2014.

[7] In 2013 it was reduced to 2,000.

[8] In 2013 there were 20,000 people living in shelters and another 120,000 inhabitants in such bad conditions that they had the right to move to in a shelter.

[9] “The dominant trend is to settle in cities, where job creation, transportation and basic living conditions require huge investments to the detriment of food production and other forms of more reasonable life styles” See Fidel Castro Ruz, “Mandela is dead: Why hide the truth about apartheid?” Granma, Havana, December 19, 2013.

[10] See Felix Contreras, “The habanero Mayito” in Remembering Mario Coyula (blog), Havana, September 8, 2014, https://mariocoyula2014.wordpress.com/2014/09/08/el-habanero- mayito-por-felix-contreras/